Chapter 2.1—On Being an Expert (at anything)

We left off last week on the cusp of discussing automaticity—the ability to do something automatically, something you don’t need to apply a whole lot of thought to.

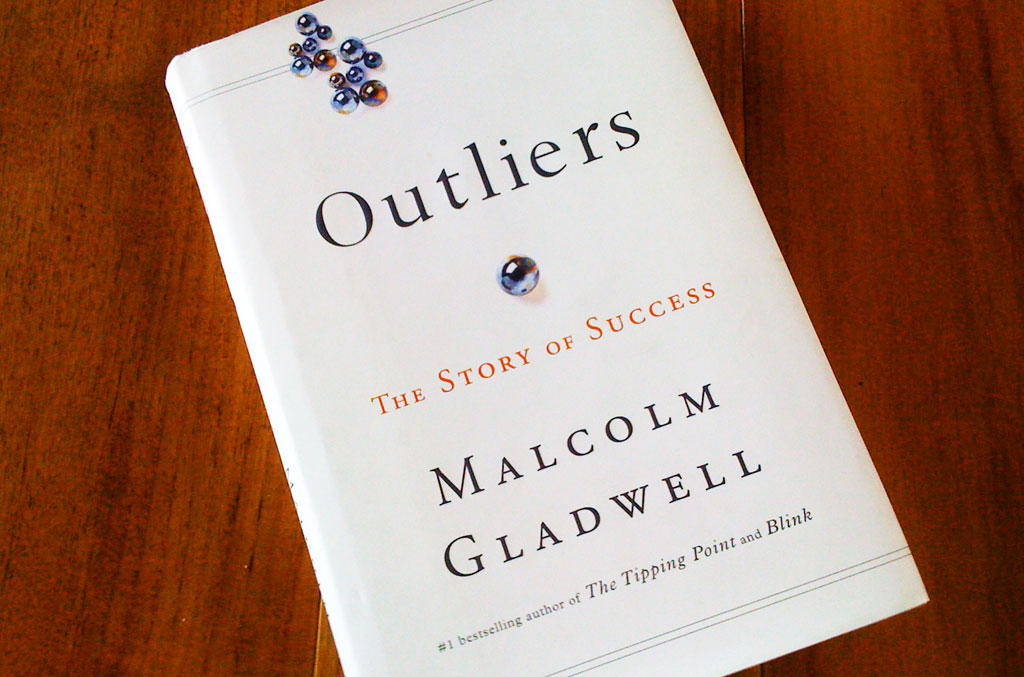

You may have heard of

Part of what Gladwell talks about in this book is based on some 1994 research by K. Anders Ericsson and Neil Charness, published in the journal American Psychologist. Gladwell took their research on musicians and spun out its implications (we’ll get back to fiber arts and doodling in a sec). What we’re left with is data on just how much time it takes to become an expert in something—he calls this the 10 years or 10,000 hours rule:

10 years or 10,000 hours

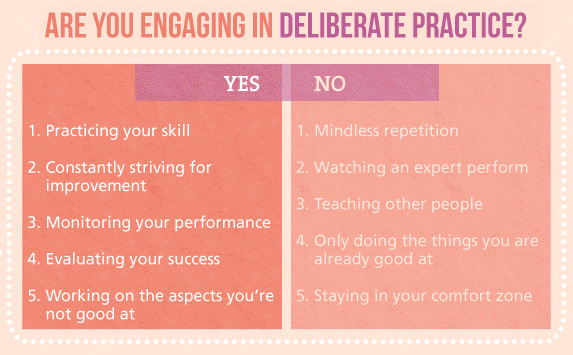

What this chart shows us is:

- the more you practice, the better you get (duh, right? Wait, because there’s more to it than that).

- if you spend under 5000 hours over the course of 16 years practicing something (how to flip a beer mat into the air and catch it?) you’ll be good enough to teach whatever it was you were practicing.

- if you spend more than 5000 hours and less than 8000 hours over the course of 16 years practicing something (piano, maybe?) you’ll be pretty darn good.

- if you spend more than 10,000 hours over the course of 16 years you’ll be the best—an expert.

Now the trick is that it isn’t JUST time that’s the factor: it isn’t 10 years of doing something makes you an expert or 10,000 hours of doing something makes you an expert. There’s more to it than that. If you spend those hours just mindlessly repeating the same things (and the same errors) you’ll be better than you were—maybe—but you won’t become an expert. (We’ll get to why this matters in a bit.) To reach those hallowed heights you have to be more than just plodding along mindlessly—you have to be engaging in Deliberate Practice or Deep Practice.

A practice where you consciously and deliberately knit the new information you’re learning together with what you learned first—your mind knits the information into a whole and new understanding. (See, back to knitting, and so soon!)

To engage in Deliberate or Deep Practice one must be über attentive and constantly pushing to learn more and do more and different.

Right about now, you’re probably thinking, “Hmmm… I wonder if that makes me an expert?”

So my question back is:

- are you always pushing yourself to try and learn new things?

- —new ways to hold your hook or needles?

- —new ways to tension your yarn?

Or are you simply making 10,000 of the same style baby hats for charity?

There’s nothing wrong with making hundreds of hats for charity… but if you don’t do more than that you won’t become an “expert.”

The good news is this:

to get the benefits I’m talking about you don’t need to be an expert.

You just need to be automatic in your knitting, crocheting, or doodling.

So that’s the question I’ll leave you with today—Where do you fall?

Are you an expert?

Are you still learning?

Or are you simply (and happily) automatic?

Next bit will appear January 17, 2014

Just for fun, I thought you also might like a graph that shows how quickly Deep Practice can move you from a novice knitter to an expert.

I know how much time I spend knitting (14-20 hrs a week, nearly all at night) and how long I’ve been knitting (off and on since I was 5) and that I’m constantly trying new techniques and patterns (to avoid boredom)… how about you?

5 Comments

I have really been enjoying your book so far and finding it very interesting. I have been knitting for about 5 years now but have been doing alot of hours, trying to try new things and learn all the time. However, I am still knitting in the same style that I have always knit in – English which might not be the most efficient or effective – up until now I have been very reluctant to try any ohter way, despite the benefits it could bring. I love that the automatic part of knitting is just that automatic and trying another way seems so clumsy and awkward. But that might be the steps I need to become an expert! (Not that I am really aiming at that – I just want to prolong my knitting life and look after my hands.) Thank you.

It’s such an interesting question, and one that we’ll get to more specifically, but I think you hit on something really important: you CAN knit automatically the way you do it right now. For getting the benefits of Cognitive Anchoring, that’s all that matters.

Now, if you’re trying to ward off arthritis or Alzheimer’s, then you’ll probably (someday) want to try Continental, or even Production/Cottage knitting sometimes called Lever knitting.

I was taught British by my grandmother, but switched to crochet for a decade. When I came back to the needles I couldn’t for the life of me remember how to hold everything—but I had gotten used to carrying the yarn in my left hand, tensioned for crochet, so that’s how I re-learned knit. Later I found out I was sometimes Combination Knitting (a la Annie Modesitt) and sometimes just doing Continental.

Trying to learn something new for muscles that are used to doing it a particular way seems MUCH more challenging to me than learning a new stitch or technique. Our muscles seem to get set in their ways even more than our brains do—which is, indeed, great for automaticity.

Not so much for ergonomics.

; )

“Just for fun, I thought you also might like a graph that shows look at how quickly Deep Practice can move you from a novice knitter to an expert.”

I think this sentence has some extra words…

Yup!

Thank you

Interesting that 20 hours a week seems to be the optimal. (If I’m reading the chart correctly.)